No nation can

simultaneously achieve low taxes, easy business conditions, and low inequality.

There are plenty of valid middle-ground combinations.

But a free market with a large social safety net (high taxes + easy business conditions) appears more effective at tackling inequality than a command economy (low taxes + stringent business regulations).

There are plenty of valid middle-ground combinations.

But a free market with a large social safety net (high taxes + easy business conditions) appears more effective at tackling inequality than a command economy (low taxes + stringent business regulations).

I’ve written before about how globalisation has actually been a spectacular success.

It has generated monumental amounts of wealth, drastically reduced poverty, and

fostered international relations. Consequently, the solution to rising

inequalities in the developed world is not a retreat from globalisation. It is to

more fairly share its benefits through the tax system – social welfare,

infrastructure, education, health care, etc.

But there is another option – regulation. Instead of

tackling inequality through higher taxes and a greater redistributive role of

government, regulating business could reign in monopoly and monopsony power[1].

This would allow workers to share more in corporate success, thereby reducing

inequality[2].

Theoretically, unions are supposed to facilitate this too, which can also be

aided through regulation. Maybe businesses can also be regulated to provide

more things like health insurance, education and training, and salary insurance

to their workers. Mechanisms like ‘developer contribution plans’ even force the

private sector to contribute to infrastructure like public transport – all of

which would help address inequality.

And through this thought, I may have discovered something

interesting – what I’m dubbing The Impossible Trinity of Inequality[3].

My hypothesis – it’s impossible to simultaneously achieve low

taxes, easy business conditions, and low inequality:

·

If you want to go the capitalist route (easy

business conditions and low taxes), you have to accept that there will be a

high level of inequality, as those that are disadvantaged or simply unlucky in

their employment or health fortunes, won’t receive the support they need;

·

If you want to have low inequality but easy

business conditions, you have to have high taxes for the government to perform

its redistributive role; and

·

If you want to have low inequality but low taxes,

you have to have stringent business regulations that protect workers from

exploitation and support social mobility.

The evidence?

I previously wrote of the link between income inequality and

government tax revenue. An intuitive enough link – governments that collect

more taxes can undertake a greater redistributive role (social welfare,

infrastructure, education, health, etc.), resulting in lower rates of

inequality.

The following graph illustrates this for the OECD countries,

with surprising statistical accuracy (0.59 is actually a pretty good

correlation).

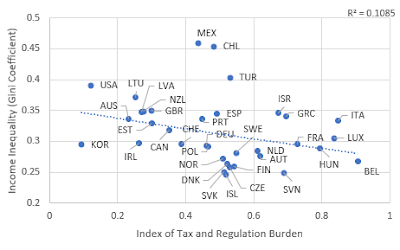

This time though, I combined an index of ‘ease of doing

business’ with tax revenue as a percentage of GDP. A lower value of this

combined index indicates lower taxes and easier business conditions. The

relationship is weaker, but still there, especially at the extremes. Countries

with the lowest taxes and easiest business conditions tended to have the

highest inequality. And those with the

highest taxes and most stringent business conditions tended to have the lowest

inequality.

And most importantly, not a single country in the OECD was

able to achieve the Impossible Trinity. No country simultaneously had low

taxes, easy business conditions and low inequality (three green boxes below).

Some countries couldn’t even achieve two – Mexico, Chile and

Turkey all enjoy low taxes, but stringent business conditions and high

inequality. And Belgium, while achieving low inequality, achieved it at the

cost of both high taxes and stringent business conditions.

But Norway and Denmark achieved both low inequality and easy

business conditions only at the cost of high taxes. The US chose another

trade-off – easy business conditions and low taxes at the cost of high

inequality.

Korea was perhaps the only major success-story outlier – it

achieved low taxes and easy business conditions at the cost of only moderate

inequality.

Several countries also chose a successful middle ground:

·

Australia and Switzerland enjoy low taxes with

average business conditions and average inequality;

·

The Czech Republic, the Slovak Republic,

Slovenia and Iceland achieved low inequality with average business conditions

and average taxes;

·

Estonia enjoys easy business conditions with

average taxes and average inequality; and

·

Canada, Ireland, the Netherlands, Poland,

Portugal, Spain and Germany were around average on all three indicators.

It’s worth noting though that no country was able to use

stringent business regulations to achieve low inequality and low taxes. This

was contrary to one of my above hypotheses. And it possibly suggests that

heavily regulating businesses is not as effective at tackling inequality as

high taxes and redistribution efforts. This is perhaps unsurprising. Income

redistribution puts resources (and therefore, choice) in the hands of

individuals. This is arguably more effective at helping those individuals than

regulation, which requires the government to attempt to decide what is best for

the individual.

Of course, these relationships aren’t perfect. And there are several different ways this data could have been sliced and diced. Further research could also yield the importance of personal vs. corporate tax rates. But this is a blog, not a submission to the Nobel Prize Committee. So for these purposes, I will still conclude thusly:

Of course, these relationships aren’t perfect. And there are several different ways this data could have been sliced and diced. Further research could also yield the importance of personal vs. corporate tax rates. But this is a blog, not a submission to the Nobel Prize Committee. So for these purposes, I will still conclude thusly:

·

You can’t achieve all three – it is indeed an

Impossible Trinity;

·

There are also plenty of valid middle-ground

combinations;

·

But a free market with a large social safety net

(high taxes + easy business conditions) like Norway and Denmark appears more

effective at tackling inequality than a command economy (low taxes + stringent

business regulations).

Task for humanity – can we turn it into The Possible

Trinity? Can we provide for everyone in society without the need for high taxes

or stringent regulations? An altruistic capitalist society, if you will.

*laughter*

[1]

The ability of businesses to control not just the price of the products they

sell, but also the price of the labour they buy.

[2] It

would also help address the ‘two-speed economy’ between corporate (and

therefore, asset market) success, and wage growth, thereby making the job of

Central Banks easier.

[3] I

first heard this expression when it referred to the Impossible Trinity of Central

Banking – the idea that an economy could not simultaneously achieve a fixed

exchange rate, open capital markets, and a Central Bank policy that targets

internal stability.

No comments:

Post a Comment