- My advice for the RBA – wait until September.

- There is little evidence that

inflation is spiralling out of control and higher interest rates won’t address

the supply chain constraints that that have been driving Australian inflation.

- Higher interest rates will, however, end

the current home building boom and suppress the wage growth for which

Australians have been waiting for almost a decade.

- The structural factors that dragged on Australia’s economy pre-pandemic still exist.

While the supply chain impacts of the war in Ukraine, and China’s latest lockdowns, have shaken my resolve on this issue, I am still a member of ‘Team Transitory’.

But I appear to be in the minority.

Market consensus has converged on the prediction that the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) will begin lifting its benchmark cash rate soon.

The RBA’s cash rate target has been set to 0.1 per cent since November 2020 and some are expecting the first hike to occur as early as June. Market expectations have the RBA’s cash rate above 3 per cent within 18 months, which would be the highest level since 2012.

The RBA needs to be very careful how far and how fast it takes this tightening cycle.

Higher interest rates won’t fix supply constraints

Higher interest rates will do nothing to alleviate the supply constraints currently driving local inflation rates. While Australian headline inflation was 1.3 per cent in the final quarter of 2021, bringing the annual rate up to 3.5 per cent, almost half of it was solely attributable to fuel prices and home building costs.

Fuel prices are entirely an international phenomenon – as the global economy started reopening in the second half of 2020, strengthening demand started pushing up fuel prices. The Russian invasion of Ukraine drove these prices even higher, given Russia’s importance to global oil production.

Higher interest rates in Australia will not fix this problem – and it looks like the latest price shock has stabilised anyway.

Home building costs have also been driven by international factors. The pandemic has produced home building booms – and associated surges in demand for home building materials like timber and steel – across the world. This saw home building costs increase by 3.8 per cent in the final quarter of 2021, bringing the annual increase to 12 per cent – the fastest rate since the early 80s. Reinforcing steel and structural timber increased especially, up by 43 per cent and 40 per cent respectively for the year.

On top of this, households shifted their spending towards goods and away from services during the pandemic, as many activities like travel, entertainment and dining out were prohibited or simply perceived as too risky.

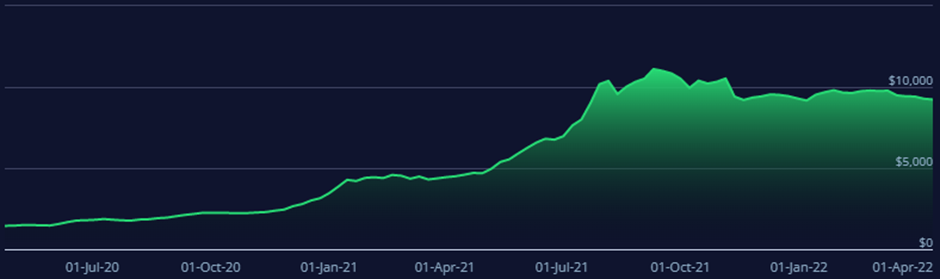

These shifts towards home building and other goods put enormous pressure on global shipping services, with the price of a 40-foot shipping container increasing from under $1,500 to more than $10,000.

Higher interest rates in Australia will not bring global shipping services back online, nor suppress the home building booms occurring overseas.

Freightos Baltic Index (FBX): Global Container Freight Index

Inflationary expectations are still anchored

There is also little evidence that current inflationary pressures are becoming dangerously entrenched.

Wage growth would be the key to such a development. In tight labour markets, workers hypothetically have the bargaining power to demand higher wages. Cost of living pressures are an added motivation to seek higher wages. This feeds back into further inflationary pressures as businesses increase the prices of their goods and services to offset the higher cost of labour. This can then feed back into further wage demands, and so on.

This is called a wage-price spiral and no economy can function with such inflation spiralling out of control. This would force the RBA to raise interest rates to suppress the economy and get inflation back under control.

There is little evidence, however, of the wage growth needed to cause such a spiral. In 2021, only one industry, ‘Accommodation and food services’, saw wage growth above 3 per cent. Wage growth in this industry has proven very susceptible to the frequent locking down and re-opening of states across Australia. Staff shortages associated with the Omicron outbreak, and extended holiday leave taken in early 2022, will also likely affect this industry.

Overall, however, wage growth at the end of 2021 was only running at an annualised 2.6 per cent. While this is the strongest wage growth since 2014, it is still far from what the RBA – and Australian workers – have been seeking for many years.

Inflationary expectations over the coming years are, consequently, hardly spiralling out of control. According to the RBA, as of March 2022, 2-year inflationary expectations from both unions and market economists were still below 3 per cent.

This is why the RBA needs to be careful with interest rates on the way up.

Higher interest rates won’t solve the supply constraints driving our current inflationary pressures and there aren’t many reasons to think these pressures are spiralling out of control anyway.

Higher interest rates will, however, bring an end to the current housing boom and suppress Australian wages.

When interest rates increase, this typically slows down house price growth and can have a negative effect on consumer confidence. Even talk of rising interest rates can have the same impact. Reduced borrowing power and lower consumer confidence makes households more hesitant to pursue large investments such as building a house. The slowing in established house prices, while the cost of new homes continues to rise, will also make banks increasingly reluctant to lend for the construction of a new home.

This reduced borrowing power extends beyond the housing industry. Household purchases of cars, furniture and appliances often involve borrowing. Businesses borrow to finance investments in property, buildings, equipment and technology. Even governments undertake cost-benefit analyses on the projects they finance through borrowing. Higher interest rates will force a reconsideration of all these decisions, reducing expenditure throughout the economy and, therefore, the number of jobs produced.

Fewer jobs means less bargaining power for workers. Australian workers that have already struggled for the best part of a decade to negotiate any substantial pay increases – pay increases that would represent precisely the thing that would allow these workers to handle the kind of cost of living pressures with which they are now faced.

Australia’s structural problems remain unaddressed.

Heading into the pandemic, Australia’s economy had been underperforming ever since the mining boom.

Before the 2019 Federal election, the RBA’s cash rate was just 1.5 per cent and the Australian economy was experiencing weak economic and wage growth, and slow productivity growth. The RBA then dropped the rate to 0.75 per cent – even before the pandemic began – and things were only slowly heading in the right direction.

This is why the market expectation of a 3+ per cent cash rate before the end of 2023 seems so excessive.

Australia’s structural problems haven’t been solved. Australia’s population is still ageing, especially with the absence of overseas migration. There is also still a significant need for infrastructure investment and microeconomic reform in areas of building approvals and urban planning frameworks, tax, energy, industrial relations, skills and training, etc. in order to catalyse the next generation of growth, productivity and prosperity.

Australians have accumulated a lot of excess savings during the pandemic and the government has spent a lot of money “building the bridge” to the other side. But none of this addresses these underlying structural concerns.

Australia also has the luxury of time.

Central banks around the world, including the US Federal Reserve, have already started increasing their benchmark interest rates in response to much higher inflation than Australia is experiencing. Even in Australia, the commercial banks have been lifting their interest rates independently of the RBA.

This allows Australia to see how effectively higher overseas – and domestic – interest rates will be in reducing demand for things like building materials and fuel. It also gives us more time to see global supply chains operating more effectively, helping to ease price pressures.

Central bank credibility is very asymmetric.

The last few decades heading into the pandemic showed clearly on which side the credibility of central banks lies. Thanks to their political quasi-independence and technical expertise, central banks across the world kept inflation – and inflationary expectations – low since the early 90s.

The challenge was on the other side, in driving full and fast recoveries.

Australia’s economy had been underperforming ever since the mining boom. The US took a full decade to recover from the GFC. In Europe, the GFC and the sovereign debt crisis were exacerbated by extreme austerity measures across the Union, and early missteps by the European Central Bank.

If the last decade has taught us anything, it’s that a recovery is hard to generate and easy to cut off.

It would be a great shame if the RBA got carried away, only to force Australia back into the environment of anaemic growth and weak wages that existed before the pandemic. All to defeat an inflation cycle that shows all the signs of being temporary.

Recent inflationary pressures are causing a lot of pain and support needs to be forthcoming – from government. Overly aggressive tightening by the RBA will only cause more pain.

For the RBA, now is the time for it to use its inflation credibility to not prematurely cut off a recovery that will generate precisely the improvement in living standards for which Australians have long been waiting.

My advice – lift the cash rate in September to 0.5 per cent, then STOP!

My official advice is that the RBA waits until September – this will give it two more readings of inflation and wage data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. If there are no signs of the economy cooling on its own, the cash rate should be lifted to 0.5 per cent. This will mostly represent a ‘symbolic’ hike to transmit to the market that the RBA is willing to act. It will also reflect the fact that we are no longer in the ‘emergency’ environment of the early pandemic.

But I don’t see why the cash rate should go any higher than this when inflationary expectations are still so well anchored.

Over the next couple of years, excess savings will be drawn down and supply chains will be functioning better. Housing markets around the world will have worked down their massive pipelines and demand pressures on building materials will have eased.

After this, Australia will still need an accommodating RBA while the necessary economic reforms and infrastructure investments are undertaken to catalyse the next generation of growth and prosperity.