Theo J Vystadt is an economic and political commentator. He investigates and discusses major national and international issues and events through the lens of economics.

Auto Ads

Saturday, 1 December 2018

Sunday, 11 November 2018

US Hawks vs NZ Doves.

Here is a link

to a brief that I wrote for the Housing Industry Association. Below is an

extended version.

New Zealand’s

apparent willingness to accept higher inflation than the US could come in handy

in the next downturn.

Terminology time! An inflation ‘hawk’ is a person who is

more worried about inflation getting too high. An inflation ‘dove’ is someone

more worried about inflation getting too low.

The US and New Zealand demonstrate both these positions

quite well.

The US is increasing interest rates while inflation barely

touches their target of 2%. Understandable – they slashed interest rates so

dramatically in the GFC and have remained so low for so long that they’re no

doubt eager to bring them back up, lest they spur some unintended imbalances,

like an over-inflated stock market or housing bubble. Still though, hawkish.

In NZ however, recent economic data is pointing to strength

– stronger economic growth, decade-low unemployment now at just 3.9%, and

employment and inflation expected to overshoot their targets on a sustained

basis. Inflation is still currently in the middle of their 1-3% target, but

given this strong data, you’d think they’d upgrade their intentions for future

interest rates rises. On the contrary, they’re being quite dovish about it.

They’re intent on keeping interest rates where they are until mid-2020 (the

same intention they had before this new stronger data came out).

As Westpac’s Dominick Stephens said:

“RBNZ

recognises that inflation pressures have built. The inflation forecast was

lifted, upside risks to inflation were emphasised more heavily, and rising

inflation was discussed up front in the document. Intriguingly, the forecast

was for inflation to rise above [their target] 2% in the medium term. [But]

RBNZ has declined to alter its [cash rate] forecast … They’re choosing

higher inflation rather than a higher [cash rate]”.

There has been commentary for several years, including from

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman, that advanced economy central banks

may have set their inflation targets too low – the US and UK at 2%, the EU under

2%, Australia 2-3%, NZ 1-3%. Again, understandable. They were set in the 1990s,

with the high inflation of the 1970s and 80s still fresh in policymakers’

minds. So they were extra keen to keep inflation under control, and believed a

1-3% buffer above zero would be enough to prevent self-fulfilling deflation

during any downturn (which can actually be just as bad and just as hard to fix

as high inflation – if not more so).

The GFC however, demonstrated that inflation can indeed,

still get too close to zero – and lower. Current inflation buffers have not

negated the dreaded ‘liquidity trap’, where central banks have already dropped

interest rates to zero but, because of inadequate inflation, real

interest rates (the gap between interest rates and inflation) are still not low

enough, making monetary policy impotent to help recover the economy.

Consequently, many advanced economies undershot their inflation targets for

most of the last decade. It turns out, even getting close to deflation –

let alone actually achieving it – can be hard to reverse.

If however, inflation targets were increased to, say, 3-5%,

that would provide a bigger buffer, without inflation getting out of control.

Another way to look at it is that the risks of central bank policy are asymmetric:

the costs of allowing inflation to venture a little too high right now are far

smaller than the risks of increasing interest rates too fast and driving the

economy back into a liquidity trap or worse, a deflationary spiral.

Perhaps this is what NZ’s central bank is thinking – an

upwards reset of their 1-3% target so they have more inflationary ammunition in

the next downturn.

Take the following hypothetical example of what NZ

and the US could be facing soon.

The US is raising interest rates rapidly to keep their

inflation rate no higher than 2%. NZ however, is raising their interest rates

more slowly, willing to accept higher inflation of, say, 4%. This means that

the real interest rate remains much lower in NZ, actually below zero and

declining for most of this period – much more stimulatory for the economy.

Therefore, in almost two years, inflation is much higher in NZ and interest

rates much lower; and in the US, inflation is much lower and interest rates

much higher.

Then in two years, where I have assumed a significant global

downturn, both the US and NZ drop their interest rates back down to zero. It

would appear the US is in a better position – they were able to drop rates a

full 5%, NZ only 2.25%. NZ however, had a much higher inflation rate beforehand

that only falls to 2%, whereas the US’s 2% inflation rate falls back to 0%.

Which means upon the downturn, NZ’s real interest rate becomes -2% and the US’s

just 0%.

This would leave the US dealing with a ‘liquidity trap’

situation. Whereas in NZ, investment would still be preferable to holding cash,

so ongoing investment in NZ would act to stabilise the economy during the

downturn. In the US, the prospect of deflation would create a disincentive to

invest[1]

and the lack of investment would be an additional headwind exacerbating the

downturn.

So even though the US can drop interest rates more

dramatically upon the downturn, NZ is able to achieve a lower real

interest rate (even though it barely decreased in the last month) and

therefore, undertake stronger stimulus – because they allowed their inflation

rate to rise further beforehand, rather than rushing to increase interest

rates.

While these numbers are somewhat arbitrary, it does

illustrate that it’s not the size of the interest rate cut you have up your

sleeve. It’s the stimulatory effect of your interest rate position after the

cut has been made – the real interest rate. 0% interest rates with 2%

inflation is more stimulatory than 0% interest rates with 0% inflation.

Furthermore, in the former case of 2% inflation, people are also less worried

about self-fulfilling deflation[2].

The implications if Australia’s Reserve Bank similarly chose

to run the economy hotter for longer are clear for the housing industry. Lower

interest rates for longer will support mortgage holders and investors alike,

thereby supporting one of Australia’s most significant industries, even in the

face of the current housing downturn.

I know all of this sounds like a bit hypothetical and

abstract. But remember, psychology is very important in economics. The

perception of being too close to deflationary territory can, all by itself,

cause an economy to fall into deflationary territory. And the housing industry,

through the mortgage market, can be the hardest hit in such an event. That’s

why an arbitrary buffer sufficiently above 0% inflation is so important.

Because perception very much becomes reality.

[1] Not

just business investment in things like property, buildings, equipment,

machinery and staff, but also household investment in property, appliances, furniture,

vehicles, etc. Even government, upon the deflationary expectation that things

will be cheaper (or at least not much more expensive) in the future, may be tempted

to put off major infrastructure investments.

[2] And

as for the unintended consequences of prolonged low interest rates, like

financial instability – interest rates are not a good tool for reigning in

asset markets, especially if they are running in the opposite direction to the

real economy (as was the case in Australia until recently with booming housing

markets). This is more a job of macro-prudential regulation and oversight, by

the central bank and/or other regulators (like APRA and ASIC in Australia). Interest

rates should be the tool used to manage the real – not financial – economy.

Saturday, 27 October 2018

The hangover.

As predicted, US soybean exports surged last quarter in an effort to beat Chinese

retaliation to Trump’s trade war (artificially inflating economic growth

figures), and have now plummeted 97% as a result.

China is weaning themselves off US soybeans, consistent with the broader global trend away

from the US.

Combined with the ongoing drag of Trump’s trade war and the

inevitable weakening of the impact of Trump’s spending spree, the US’s current

binge can’t go on much longer. The hangover is coming.

Sayonara, America!

Just as predicted, while Trump continues his trade war, the rest of the world continues to move on

without him.

This time … fierce rivals China and Japan.

China, Japan Vow to Cooperate as Trump Hits

Both on Trade

By Isabel Reynolds and Emi Nobuhiro

26 October 2018 12:50 PM AEDT Updated on 26 October 2018 11:07 PM AEDT

By Isabel Reynolds and Emi Nobuhiro

26 October 2018 12:50 PM AEDT Updated on 26 October 2018 11:07 PM AEDT

China and Japan

capped a restoration of ties with agreements on everything from currency swaps

to ocean rescue Friday, a thaw that comes as President Donald Trump seeks

better trade terms with both nations.

Shinzo Abe

became the first Japanese prime minister to pay an official visit to China in

seven years, as Asia’s two largest economies sought to play down disagreements

that have hindered relations for decades. They both reiterated support for free

trade and called for the early conclusion of a regional trade pact with 16

Asia-Pacific nations that doesn’t include the U.S.

After Abe and

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang commemorated the 40th anniversary of a peace and

friendship treaty on Thursday, the two held formal talks on Friday and oversaw

the signing of cooperation agreements between the two governments. Abe then met

and dined with President Xi Jinping, marking a new high point for a

relationship he has long sought to mend.

At that

meeting, Xi said the two countries are becoming increasingly interdependent and

that they should be partners rather than threats to each other, according to a

Japanese official. He also said China’s Belt and Road initiative provides a

platform for cooperation and that the nations will adhere to free trade and

face global challenges together.

Abe was

accompanied to China by foreign and trade ministers and a 500-strong business

delegation. The two sides signed 50 cooperation agreements, including reviving

a 200 billion yuan ($29 billion) currency-swap deal. The neighbors also agreed

to discuss establishing a clearing bank for offshore yuan and cooperation

between Japan’s Financial Services Agency and the China Securities

“China is

willing to work together with Japan to take Sino-Japanese relations back to a

normal track, maintaining stable, sustainable and healthy development and

making new progress,” Li said during an appearance with Abe on Friday. Both

sides believed that stable relations were important and that they should take

“concrete measures” to become cooperative partners, he said.

Japan’s

relations with its biggest trading partner turned hostile in 2012, when it

nationalized part of a disputed East China Sea island chain, sparking sometimes

violent protests and damaging business ties. Since taking office at the end of

that year, Abe has consistently sought meetings with Chinese leaders, even as

anger simmered over the territorial and other disputes.

Abe said he

sought frank talks with Xi and Li covering North Korea and trade issues. The

two sides also agreed to cooperate on search-and-rescue operations at sea, and

assist each other in developing health care and elderly care services.

In a speech to

a business forum on Friday, Abe harked back to Japan’s role in providing aid

and private sector investment from the 1980s that helped turn China into an

economic powerhouse.

“The Japanese

government and companies invested and worked with the Chinese people toward

modernization,” he said. “Seeing how China has developed is a source of pride

for Japan as well.”

The thorniest

issues between the two sides had so far received little mention. There were no

immediate agreements on how to handle the territorial dispute, or the issue of

gas resources around the disputed sea border between their exclusive economic

zones.

“The difficult

issues are going to stay,” said Akio Takahara, a professor at the University of

Tokyo, adding that he expected relations to remain cordial at least until Xi

visits Japan, which he is expected to do for the Group of 20 summit in Osaka

next year.

“The Chinese

Communist Party always has this history card against Japan in their pocket,”

Takahara said. “Whenever they feel the need to take it out, I’m sure they will

do that.”

What do you do when your argument can't stand on its own?

Interesting article by Catherine Rampell about how

Republicans, instead of attempting to defend their policies on their own merit,

are simply lying about what they want to achieve. With regard to health care

for example, Republicans have long desired (and attempted) Obamacare’s destruction.

But instead of trying to justify this position, they actually claim they’re

trying to do the exact opposite:

“For instance,

they might argue that in their ideal capitalist society, it’s not government’s

job to shield Americans from the financial risks of serious health conditions.

Every man (or woman) is an island, responsible for his or her own health care.

If expensive illnesses befall some unlucky members of society, and they lacked

the foresight or haven’t saved enough to plan for this risk on their own, then

too bad. Life ain’t fair.” Catherine Rampell

But instead of doing this, Republicans still maintain that

they want to do things like protect those with pre-existing conditions, despite

continued efforts to the contrary.

I made essentially the same point about Trumpcare last September.

“If Republicans

actually justified Trumpcare by saying that health care is not the role of

government, but the responsibility of the individual, and that the risk of

sickness, bankruptcy and death that comes from this is the inevitable price we

should pay for our 'freedom', then I could respect it.

I wouldn't

agree with it. Both socially and economically, public health care makes sense.

But at least their policy narrative would be consistent with their ideology.

But from

beginning to end, Republicans have claimed that Trumpcare will provide BETTER

health care to MORE people at LOWER cost, when so much evidence (including the

CBO and the insurance industry itself) seems to suggest WORSE, LESS and HIGHER.

So are they

being dishonest about their ideology or ignorant about their policy?”

Catherine Rampell thinks the former.

Republicans are mischaracterizing nearly all

their major policies. Why?

By Catherine Rampell

October 25 at 6:45 PM

By Catherine Rampell

October 25 at 6:45 PM

Republicans

have mischaracterized just about every major policy on their agenda. The

question is why. If they genuinely believe their policies are correct, why not

defend them on the merits?

Consider the

GOP tax cuts. Last year, Republicans said their bill would primarily benefit

the middle class, pay for itself and raise President Trump’s taxes, among other

claims.

Not one of

these contentions is remotely true.

A more honest

defense — and one occasionally revealed via accidentally-told-the-truth Kinsley

gaffes — might have been something like: We want to let rich people keep more

of their money, regardless of the cost to Uncle Sam. We want this both because

we (unlike most of the public) think that’s fair, and also because our donors

are demanding a return on their investment in us. Plus, maybe it’s a good thing

to reduce government revenue; that gives us motivation to “starve the beast” and

cut the safety net, which we think is a drag on the economy that protects

people from the consequences of their poor life choices.

Likewise with

family separations, a policy Trump is considering reviving.

In the spring,

the administration systematically ripped immigrant children from their mothers’

breasts with no plan for tracking where they ended up or how to reunite these

families. The rationale, as gaffingly revealed by White House Chief of Staff John

F. Kelly, was that such cruelty would deter asylum seekers.

But when voters

recoiled, the administration explained things differently. Officials

alternately lied that the policy was designed to help children, was actually a

Democratic policy or didn’t exist at all.

Lately, the

biggest GOP lies involve health care — the top midterm issue for voters — and

especially how Republicans would treat Americans with costly medical issues.

The public has

had ample opportunity to learn where Republicans stand on protections for those

with preexisting conditions. The party spent the past eight years, after all,

trying to repeal the Affordable Care Act, including these particular (very

popular) provisions.

And while

Republicans failed to repeal Obamacare legislatively, they’ve found other means

to undermine its protections.

For instance,

the Trump administration has expanded the availability of junk insurance. These

cheap plans look like regular insurance but actually cover little to no care,

something you would notice only if you read the fine print. Such policies are

not required to accept enrollees with preexisting conditions or to pay claims

related to preexisting conditions — even if the preexisting illness hadn’t even

been diagnosed at the time of enrollment.

These policies

threaten coverage another way, too. Because they siphon young, cheap and

healthy people off the Obamacare exchanges, they drive up prices on (real)

insurance and thereby put coverage further out of reach for people who are

sicker and older.

On Monday, the

administration issued new regulatory guidance that will effectively allow

states to nudge more people into these junk plans. And that’s just one of many

measures the administration has taken that will destabilize the individual

marketplaces and jack up unsubsidized premiums for people with preexisting conditions.

There’s clearly

appetite among state-level Republicans to roll back such protections, too.

In fact, 20 red

states have sued the federal government, arguing that Obamacare, including its

preexisting-condition protections, is unconstitutional. Administrations are

supposed to defend laws passed by Congress, but on these provisions, the Trump

administration has refused.

And yet, Trump

continues to argue that “Republicans will totally protect people with

Pre-Existing Conditions, Democrats will not!”

When Trump made

this claim at a rally in Wisconsin, he was echoed by Gov. Scott Walker (R), who

urged the crowd: “Don’t believe the lies. We will cover people with preexisting

conditions.”

This despite

the fact that Walker authorized his own attorney general to join that 20-state

lawsuit. But Walker is far from alone. Across the country, Republican

politicians shamelessly conceal their track record on this issue.

Once again,

rather than misrepresenting their own positions, Republicans could try to

defend them on the merits.

For instance,

they might argue that in their ideal capitalist society, it’s not government’s

job to shield Americans from the financial risks of serious health conditions.

Every man (or woman) is an island, responsible for his or her own health care.

If expensive illnesses befall some unlucky members of society, and they lacked

the foresight or haven’t saved enough to plan for this risk on their own, then

too bad. Life ain’t fair.

You might

wonder if maybe Republican politicians are mischaracterizing so many of their

own positions because they don’t fully understand them. But given that

Republican leaders have occasionally blurted out their true motives — on taxes,

immigration and, yes, even health care — this explanation seems a little too

charitable.

Republican

politicians aren’t too dumb to know what their policies do. But clearly they

think the rest of us are.

Sunday, 30 September 2018

The Impossible Trinity

No nation can

simultaneously achieve low taxes, easy business conditions, and low inequality.

There are plenty of valid middle-ground combinations.

But a free market with a large social safety net (high taxes + easy business conditions) appears more effective at tackling inequality than a command economy (low taxes + stringent business regulations).

There are plenty of valid middle-ground combinations.

But a free market with a large social safety net (high taxes + easy business conditions) appears more effective at tackling inequality than a command economy (low taxes + stringent business regulations).

I’ve written before about how globalisation has actually been a spectacular success.

It has generated monumental amounts of wealth, drastically reduced poverty, and

fostered international relations. Consequently, the solution to rising

inequalities in the developed world is not a retreat from globalisation. It is to

more fairly share its benefits through the tax system – social welfare,

infrastructure, education, health care, etc.

But there is another option – regulation. Instead of

tackling inequality through higher taxes and a greater redistributive role of

government, regulating business could reign in monopoly and monopsony power[1].

This would allow workers to share more in corporate success, thereby reducing

inequality[2].

Theoretically, unions are supposed to facilitate this too, which can also be

aided through regulation. Maybe businesses can also be regulated to provide

more things like health insurance, education and training, and salary insurance

to their workers. Mechanisms like ‘developer contribution plans’ even force the

private sector to contribute to infrastructure like public transport – all of

which would help address inequality.

And through this thought, I may have discovered something

interesting – what I’m dubbing The Impossible Trinity of Inequality[3].

My hypothesis – it’s impossible to simultaneously achieve low

taxes, easy business conditions, and low inequality:

·

If you want to go the capitalist route (easy

business conditions and low taxes), you have to accept that there will be a

high level of inequality, as those that are disadvantaged or simply unlucky in

their employment or health fortunes, won’t receive the support they need;

·

If you want to have low inequality but easy

business conditions, you have to have high taxes for the government to perform

its redistributive role; and

·

If you want to have low inequality but low taxes,

you have to have stringent business regulations that protect workers from

exploitation and support social mobility.

The evidence?

I previously wrote of the link between income inequality and

government tax revenue. An intuitive enough link – governments that collect

more taxes can undertake a greater redistributive role (social welfare,

infrastructure, education, health, etc.), resulting in lower rates of

inequality.

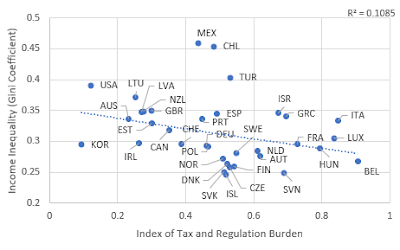

The following graph illustrates this for the OECD countries,

with surprising statistical accuracy (0.59 is actually a pretty good

correlation).

This time though, I combined an index of ‘ease of doing

business’ with tax revenue as a percentage of GDP. A lower value of this

combined index indicates lower taxes and easier business conditions. The

relationship is weaker, but still there, especially at the extremes. Countries

with the lowest taxes and easiest business conditions tended to have the

highest inequality. And those with the

highest taxes and most stringent business conditions tended to have the lowest

inequality.

And most importantly, not a single country in the OECD was

able to achieve the Impossible Trinity. No country simultaneously had low

taxes, easy business conditions and low inequality (three green boxes below).

Some countries couldn’t even achieve two – Mexico, Chile and

Turkey all enjoy low taxes, but stringent business conditions and high

inequality. And Belgium, while achieving low inequality, achieved it at the

cost of both high taxes and stringent business conditions.

But Norway and Denmark achieved both low inequality and easy

business conditions only at the cost of high taxes. The US chose another

trade-off – easy business conditions and low taxes at the cost of high

inequality.

Korea was perhaps the only major success-story outlier – it

achieved low taxes and easy business conditions at the cost of only moderate

inequality.

Several countries also chose a successful middle ground:

·

Australia and Switzerland enjoy low taxes with

average business conditions and average inequality;

·

The Czech Republic, the Slovak Republic,

Slovenia and Iceland achieved low inequality with average business conditions

and average taxes;

·

Estonia enjoys easy business conditions with

average taxes and average inequality; and

·

Canada, Ireland, the Netherlands, Poland,

Portugal, Spain and Germany were around average on all three indicators.

It’s worth noting though that no country was able to use

stringent business regulations to achieve low inequality and low taxes. This

was contrary to one of my above hypotheses. And it possibly suggests that

heavily regulating businesses is not as effective at tackling inequality as

high taxes and redistribution efforts. This is perhaps unsurprising. Income

redistribution puts resources (and therefore, choice) in the hands of

individuals. This is arguably more effective at helping those individuals than

regulation, which requires the government to attempt to decide what is best for

the individual.

Of course, these relationships aren’t perfect. And there are several different ways this data could have been sliced and diced. Further research could also yield the importance of personal vs. corporate tax rates. But this is a blog, not a submission to the Nobel Prize Committee. So for these purposes, I will still conclude thusly:

Of course, these relationships aren’t perfect. And there are several different ways this data could have been sliced and diced. Further research could also yield the importance of personal vs. corporate tax rates. But this is a blog, not a submission to the Nobel Prize Committee. So for these purposes, I will still conclude thusly:

·

You can’t achieve all three – it is indeed an

Impossible Trinity;

·

There are also plenty of valid middle-ground

combinations;

·

But a free market with a large social safety net

(high taxes + easy business conditions) like Norway and Denmark appears more

effective at tackling inequality than a command economy (low taxes + stringent

business regulations).

Task for humanity – can we turn it into The Possible

Trinity? Can we provide for everyone in society without the need for high taxes

or stringent regulations? An altruistic capitalist society, if you will.

*laughter*

[1]

The ability of businesses to control not just the price of the products they

sell, but also the price of the labour they buy.

[2] It

would also help address the ‘two-speed economy’ between corporate (and

therefore, asset market) success, and wage growth, thereby making the job of

Central Banks easier.

[3] I

first heard this expression when it referred to the Impossible Trinity of Central

Banking – the idea that an economy could not simultaneously achieve a fixed

exchange rate, open capital markets, and a Central Bank policy that targets

internal stability.

Wednesday, 26 September 2018

International trade is not a prisoners’ dilemma – cheating is how you lose.

The final sentence of this article poses a question: “Why, when America

is acting outside the rule book, should others stick to it?”

This is a dangerous thing for The Economist – formerly a

champion of free trade and State inaction – to say.

Firstly, China itself is definitely not innocent of playing

outside the rule book – think counterfeited US luxury goods, bootlegged Hollywood films, fake Apple stores, trade secrets pilfered from cutting edge US tech companies, forcing US firms to hand over their technology if they wanted to operate in China. But as I’ve made clear before,

the solution was never to trigger a trade war, but to create a coalition of

trading partners that would put pressure on China to behave better – something

like the TPP that Trump abandoned. This would have been far more likely to

generate cooperation rather than escalation.

Now to the question of why we should all keep playing by the

rules if one or two players have already started cheating. This is the common

misconception about world trade, and exactly how to trigger escalation and cause

everything to get worse.

Game theory has a scenario called the ‘prisoners’ dilemma’,

where two arrested criminals have the choice to ‘rat out’ one another, or

remain silent. Here are the possible outcomes:

·

Both stay silent, and only get 1 year in prison

for a lesser crime;

·

Only one criminal ‘rats’, resulting in the ‘rat’

going free and the one who remained silent getting 5 years in prison; or

·

Both criminals ‘rat’, resulting in both going to

prison for 3 years (less than the 5 years because they cooperated).

So even though the best outcome for both of the criminals combined

is to stay silent, the incentive for each criminal, no matter what the other

one does, is to ‘rat’:

·

If you assume your partner will stay silent, you

will go free by ‘ratting’;

·

If you assume your partner will ‘rat’, you also ‘ratting’

will give you a lesser prison term than staying silent.

Criminal 2

|

|||

Stay Silent

|

Rat

|

||

Criminal 1

|

Stay Silent

|

1,1

|

5,0

|

Rat

|

0,5

|

3,3

|

|

Applying this logic to international trade, we could say

that the optimal outcome is for everyone to cooperate (free trade), but that

everyone has an incentive to cheat, always, especially if someone has already

broken the rules.

But this is wrong.

During a trade war, retaliation (cheating in response to

someone else cheating) causes a worse outcome for everyone, including the ‘justified’ retaliator, as follows (the

numbers are arbitrary, but think of them as percentage changes in your country’s

GDP):

Country 2

|

|||

Cooperate

|

Cheat

|

||

Country 1

|

Cooperate

|

10,10

|

7,12

|

Cheat

|

12,7

|

5,5

|

|

·

Both countries gain 10% in GDP by trading

freely;

·

If one country imposes tariffs, they gain 12%

while the other still gains, but only 7%;

·

If both country’s cheat, they both only gain 5%.

So in international trade, even when your partners cheat, it

is still in your best interests to be able to import freely. Escalating a trade

war is never rational, even if it means swallowing a little pride.

Furthermore, the above example assumes that a country like

the US can benefit from being the only one who imposes tariffs because of their

size and market power. But as the steel and aluminium tariffs demonstrated,

even in a country with the US’s market power, such poorly targeted tariffs

damaged US companies that use steel and aluminium as inputs (e.g. the auto

industry) far more than it helped steel and aluminium producers (by an

estimated factor of 16:1!).

So the incentive to cheat is even more questionable, even if you can get away

with it.

So this is not the traditional ‘prisoners’ dilemma’ – yes, we

are better off cooperating, and if we have any market power, we do have an

incentive to cheat, just like the traditional game. BUT, the costs of the

escalation of a trade war rapidly increase as more players cheat, meaning that

it was better to just deal with one cheater than many.

In other words:

·

Both sides combined are better off cooperating (like

the prisoners’ dilemma);

·

If you assume your trade partner will cooperate,

you may have an incentive to cheat (like the prisoners’ dilemma);

·

But if you assume your trade partner will cheat,

you are better off not escalating and

instead, cooperating (unlike the prisoners’

dilemma).

As I wrote before about retaliating to Trump’s tariffs, we should have left it.

Saturday, 15 September 2018

The collapse of Lehman Brothers and the subsequent GFC.

10 years on we need to get the public on board with how policymakers responded.

As I’ve written before, the GFC was first and foremost an economic problem, and

a moral problem second. During the initial panic, and early in the recovery,

the economic problem must be dealt with first – emergency liquidity, targeted

bailouts, rock bottom interest rates, fiscal stimulus. THEN, once the economy

is on solid-footing again, the moral problem can be addressed – debt reduction,

financial regulation and oversight, and retribution against those responsible

can take place[1].

By and large, addressing the economic problem first is what

the US Federal Reserve and Government did. Consequently, unemployment peaked at

10% and the actual recession was short-lived. But there were subsequent

failures – both economic and moral. The fiscal support was short-lived and

inadequate, so the recovery took much longer than it should have. Furthermore,

financial sector reform – while things like the Dodd-Frank Act were a good

start – arguably didn’t go far enough to prevent a future crisis. And

importantly – and what most public opinion truly despised – virtually no one in

the financial sector was held accountable for the GFC. All the public saw was

bailouts, and bad people getting golden parachutes.

Consequently, despite the absolute necessity of these

emergency measures to stave off a much larger crisis (Depression 2.0), public opinion

now is very unfavourable to doing these things again if the occasion calls for

it.

But we can see what happens if policy is impotent during

such a crisis. The Great Depression was a great example – Central Banks obsessed

with maintaining their exchange rates relative to the Gold Standard, resulting

in higher interest rates, inadequate crisis liquidity and consequently, total financial

system collapse, Depression and widespread deflation, and 25% unemployment in

the US.

And following the GFC, Europe offers another case study of

policy impotence. The European Central Bank was slower to react in monetary

terms, more punitive measures were imposed against the banks, and governments reacted

in the reverse direction in fiscal terms with austerity. Consequently,

prolonged recession and deflation, and mass unemployment ensued, comparable

(even worse) than the Great Depression. One of the only silver linings was

Europe having a much more supportive social safety net this time around

compared to the Great Depression. So the human suffering and hardship could still have been worse.

As I’ve also mentioned before, public opinion matters. It’s not enough to say

that, as long as the right people are in power, they will do the right thing,

regardless of what ‘Joe Public’ thinks. I mean, Ben Bernanke faced scorched-earth

opposition to his crisis measures, but he still undertook them. But this is not

enough. Because if ‘Joe Public’ disapproves this time around, he will vote

accordingly, and during the next crisis we may see completely different types

in power. And that’s what we’ve seen. Following the GFC, a global wave of populism

has swept Europe, the US and even Australia. Brexit and Trump are merely the

most high-profile examples of this. But one of the telling characteristics of

such populism is a distrust of technical expertise – precisely the expertise

that is more likely to make the right decisions even when they are unpopular.

And if another crisis comes along (look out, Australia), and these new

populist powers refuse to provide the necessary (and often unpopular) support

because they find it simply unacceptable to bail out the financial sector

again, we are in trouble.

The public needs to be shown how these tough decisions were

the right ones. Yes, a lot more could have been done to speed up the recovery

(or in the case of Europe, not make things worse), reign in the financial

sector and punish those responsible. But if these new populist powers encounter

another crisis, and insist on addressing the morality issue before the economic

one, they will literally make the situation worse, especially for those they

claim to want to protect. And there will be no guarantee that those responsible

for the crisis in the first place will be caught up in the downward spiral.

Policymakers need to be able to quickly do the right thing without

having to justify it to politicians or the public. But once the dust settles, they

need to convince the public it was the right thing – before the time comes to do

the right thing again.

It’s always tempting to want to teach the bad guys a lesson –

but not at the expense of the rest of us.

Also see Catherine Rampell’s piece, Heaven help us in the next financial crisis.

[1] Technically,

as long as it doesn’t restart a panic and/or jeopardise the subsequent

recovery, regulation, oversight and retribution may begin sooner. But not debt

reduction.

Look who have just become friends.

Many, including myself, have said that Trump’s alienation of allies risks undermining Western alliances and creating a void that someone else will inevitably fill.

And look who have just become friends. China and Russia are:

- Presenting a united front against protectionism and unilateralism;

- Undertaking joint military exercises;

- Increasing the use of their own currencies in their growing cross-country trade, rather than the US dollar.

- Presenting a united front against protectionism and unilateralism;

- Undertaking joint military exercises;

- Increasing the use of their own currencies in their growing cross-country trade, rather than the US dollar.

It seems Trump’s trade war on China and sanctions on Russia (though I’m not opposed to the latter) have given Russia and China a common enemy.

How effectively can the rest of the world reign in the strategic ambitions, interference and unfair trade practices of two parties that are now cooperating, when our biggest ally is picking a fight with his own side?

Friday, 7 September 2018

Is it too late to prevent an Australian recession?

My newfound pessimism.

Until recently, I’d been quietly optimistic about Australia’s

future as we continue our transition away from the mining and resources boom. That’s

not to say there weren’t issues. The real economy had been sluggish for a while.

Housing markets got dangerously hot, especially Melbourne and Sydney. Australian

households are among the most indebted in the world. And wage growth still remains low despite economic

growth strengthening and unemployment falling towards 5%.

But I still had confidence. The RBA, APRA and ASIC had

effectively reigned in the property markets. And they did this with their

macro-prudential regulation and oversight. This meant the RBA didn’t have to raise

their own interest rates (which would have hurt the already sluggish real economy). Other sectors were

rising to take the place of the mining and resources sector, including education (Australia’s

third largest export). And the government had enacted its own fiscal stimulus

in the form of public infrastructure works, especially public transport.

All that was required was for wage growth to pick up again.

This would allow households to gradually pay down their debt levels without necessitating

a major correction. But time seems to be running out.

First, wage growth is still stubbornly low. And if

the US is any indication (4% unemployment and similarly slow wage growth), Australia

may still have a few years

before real wage growth emerges. And new information has revealed the Australian households’ savings

rate is now at a 6-year low. When that source of spending dries up, we’ll need

another.

Second, household debt may have reached a tipping

point. Not just because it is already so high. But because for many households,

it’s about to become a whole lot more expensive. One of the concerns of the

RBA, APRA and ASIC over the past few years has been the proliferation of

interest-only loans. Commercial banks gave a lot of mortgages that, for the first 5 or so years, didn’t require any of the principle to be paid. As the name suggests, only interest

needed to be paid. For financially savvy and ideally already-wealthy

individuals, this was a useful new source of financial flexibility.

Unfortunately, for many borrowers, it just delayed the inevitable realisation

that it was more than they could afford. And in 2019, 900,000 of these interest-only loans are due to expire. This will force the average interest-only

borrower to suddenly pay an extra $400 a month in principle. This potential

wave of defaults may not undermine the financial sector itself[1].

But the shock to household consumption and by extension, business investment,

could be significant.

Third, interest rates are rising around the world, driven

by the US. The Federal Reserve was already on a path towards normalising

interest rates. And the US government’s current spending spree – to the extent

it drives short term economic activity – is likely to accelerate this. The

additional debt the US government will have to issue will have the same impact

(more government bonds depresses their price and raises their yield – a key global

interest rate). And on top of the Fed’s cash rate, the Fed will also want to start

reducing the balance sheet they drastically expanded following the GFC. Again,

a sudden influx of these assets onto the market will depress their prices and

raise their yields. The RBA does have 1.5% worth of scope to drop our domestic

interest rates further (technically even more if they’re willing to consider

negative interest rates). But that is a lot of upward potential global pressure

to offset.

Fourth, any major economic downturn in Australia will

automatically worsen the federal budget. Income growth will slow or reverse,

causing government revenue to do the same. And outlays will expand as more

people require income and unemployment support. This is an ‘automatic stabiliser’

designed to stimulate the economy during a downturn and cool it during a boom.

Unfortunately, I’m concerned our conservative government may use that as an

excuse to tighten the budget further. This is the opposite of what is

needed during an economic downturn. And it’s especially unjustified given Australian

government debt is low by international standards and low relative to Australian

households. Their borrowing costs are also still low.

Slow wages, high debt, a sudden spike in local mortgage

costs, increasing pressure on international borrowing costs, and doubts

surrounding our government’s fiscal response – seems like the perfect recipe

for a downward spiral. And I haven’t even mentioned the potential for Australia

to get caught up in the US’s global trade war.

But this is not a “recession we have to have”. As I’ve written before, financial

crises – even Depression- or GFC-scale ones – can be managed without widespread

disaster and hardship. The Reserve Bank can provide the emergency liquidity and

(if necessary) the targeted bailouts to support the financial sector through

the initial panic[2].

Interest rates – both short term and long term – can be lowered, even into

negative territory. The Federal Government can take the opportunity (and

necessity) to borrow at these very low rates and enact even more significant

infrastructure investments. Targeted tax cuts are also an option. And once the

economy is back on solid footing (i.e. business, industry and households have

resumed as the main driving force) – but not before – debts can be paid down

and financial market regulation and oversight improved to avoid a future repeat

of such a crisis.

But this requires a lot of pieces in the right place at the

right time – and no small amount of luck. Hence my increasing pessimism.

[1]

Australian banks are quite well capitalised, thanks in part to additional

requirements placed on them by APRA in the last few years to hedge against

potential liquidity problems in the future.

[2]

Though as mentioned earlier, I don’t think the financial sector itself is in

significant systemic danger.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)